Introduction

For years, educational publishers serving kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) eagerly bundled digital goodies with their textbooks at no extra charge. From CD‑ROMs packed with interactive lessons to free online portals for teachers, these early digital offerings were often given away as add-ons to boost print textbook adoption. The strategy seemed sound at the time: sweeten the deal on a print textbook adoption by throwing in cutting-edge digital resources. However, this well-intentioned strategy planted the seeds of a major industry challenge. It entrenched a perception among schools and educators that digital resources should come at no cost, just an expected part of the package. Now, as publishers invest heavily in sophisticated digital platforms – from adaptive learning software to AI-driven tutoring – they face customers conditioned to expect digital for free.

In this article, we’ll explore how major K–12 publishers like Scholastic, Pearson, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH) gave away digital content in the early days and the long-term repercussions on customer expectations, revenue models, and profit margins. We’ll draw on historical examples (remember those free CD‑ROMs in the back of textbooks?) and direct quotes from industry leaders on the painful digital transformation that followed. In the second half, we’ll look at how adaptive learning and AI-powered personalization are increasing the value of digital tools, offering a path to re-monetize what was once given away. We’ll highlight successful case studies and product shifts – instances where data-driven personalization boosted learning outcomes and revenues – pointing the way for publishers to recover from the “free digital” legacy. The tone here is analytical and authoritative, aimed at product managers, digital strategists, and executives navigating the educational publishing sector’s next chapter.

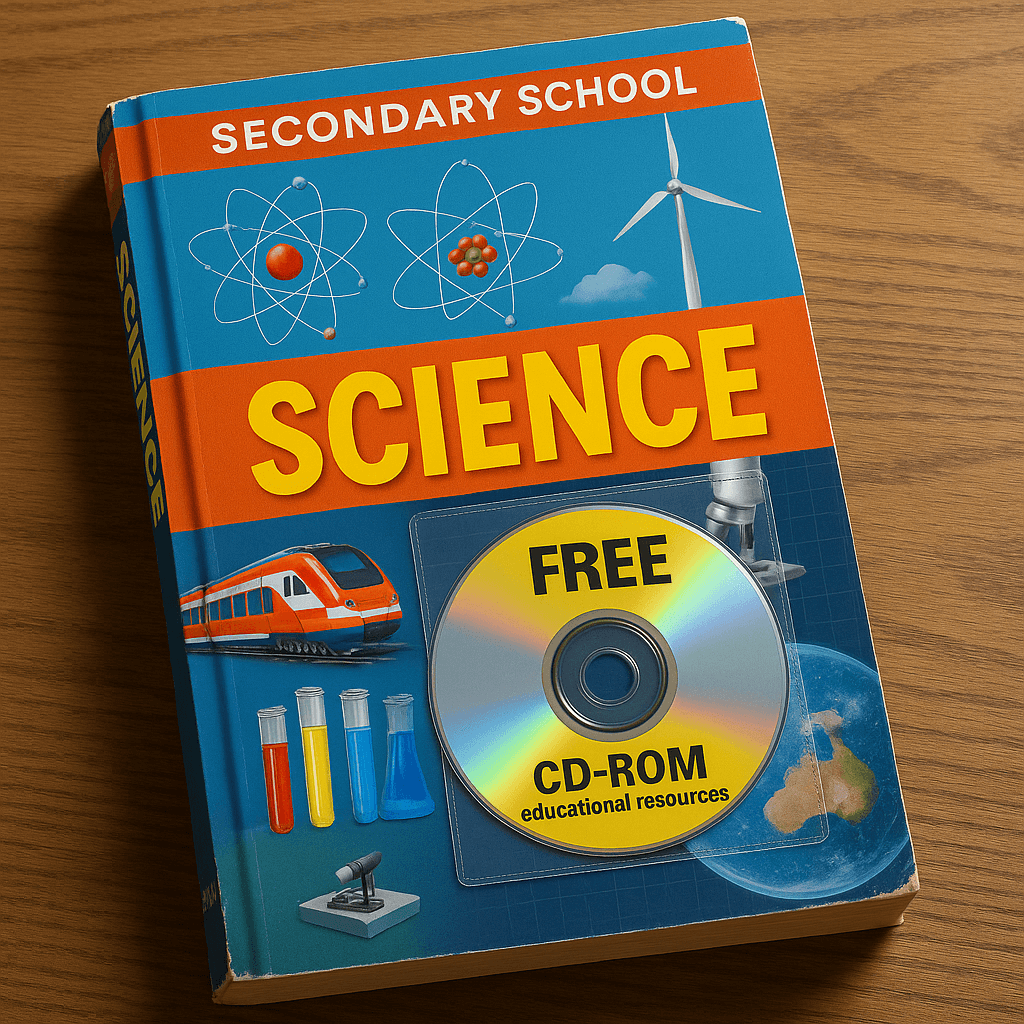

Giving It All Away: A Brief History of Free Digital Content in K–12

In the 1990s and 2000s, as education technology first bloomed, many K–12 publishers treated digital content as a promotional extra. Print textbooks remained the revenue engine, and digital resources were often viewed as ancillaries to spice up the core print product. A U.K. study in 2009, for example, found that combining print textbooks with e-textbook access (“bundled print and e-textbooks”) was more successful in driving sales than selling e-textbooks standalone. In practice, this meant a school might purchase a class set of books and receive a CD‑ROM or website login at no additional cost. Publishers discovered that such bundles not only added perceived value but also helped combat the used textbook market – titles available digitally saw up to a 68% drop in used-print sales (since students with digital access didn’t need second-hand books). For publishers, that was a win at the time, as it drove new textbook sales and discouraged reuse.

By the mid-2000s, it became common for “blended” products to dominate K–12 curriculum offerings. A 2007 UK competition commission report noted that most educational publishers were producing complete programs that included “textbooks, teachers’ material, online resources and supplementary material” as a package. In other words, rather than selling digital components separately, the majority of resources were offered as blended products or full programs. If a district adopted a new math program from Pearson or HMH, they expected not just student books and teacher’s editions, but also DVDs, CD‑ROMs, or website subscriptions thrown in. Sales reps for the big publishers leaned into this: DO you need interactive practice software or a test generator? It’s bundled for free if you choose our textbook.

Publishers like Scholastic, though better known for trade books and book fairs, also dabbled in free digital supplements. When Scholastic was still in the textbook business in the 1990s, it similarly packaged technology with its print basal programs. (Scholastic actually exited the commoditized textbook business in 2000 to focus on alternative educational technology and services.) Even outside of textbooks, Scholastic spent decades giving teachers free digital content on its websites – from printable worksheets to classroom activities – partly as a brand goodwill exercise. These freebies further ingrained the idea that digital teaching materials should not come with a price tag attached.

From the publishers’ perspective back then, these decisions were rational. The market demand for digital was unproven, and tacking a CD‑ROM onto a textbook adoption was an easy way to differentiate their product without complex pricing models. The revenue from the hefty textbook sale would cover the cost. And initially, the digital content itself was relatively cheap to produce (often static resources or simple software). The true costs – maintaining and updating software, developing robust platforms, providing technical support – would balloon later as digital offerings became more sophisticated.

Customers Trained to Expect “Digital = Free”

The unintended consequence of years of bundling digital add-ons at no obvious cost was a profound shift in customer expectations. School districts and educators came to see digital components as an entitlement – something that should be included with a core curriculum purchase. Paying separately (or paying a lot) for digital curriculum felt foreign. After all, for a decade or more, they had been handed CDs and website passwords “on the house.” When publishers later began offering standalone digital products or more advanced platforms, many customers balked at the pricing because they had mentally anchored digital resources at a price of $0.

This dynamic became painfully clear as digital content started to overtake print in strategic importance. Surveys showed that affordability quickly rose to the top of educators’ concerns about digital materials. In a 2015 Education Week Research Center survey, 51% of teachers and about 40% of administrators said the cost of desired digital content was unaffordable. Affordability was ranked the #1 challenge in using digital instructional content, above even issues like device access or training. In other words, many schools wanted more digital resources but struggled to budget for them – a likely legacy of having received so much for free. The sticker shock was real.

Compounding this issue was the rise of Open Educational Resources (OER) in the 2010s. Governments and nonprofits began promoting free, openly licensed digital textbooks and lessons. Publishers suddenly faced not only their own giveaway history, but new competitors that were born free. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s annual report explicitly notes that open educational resources – “free, digital solutions that range from supplemental resources to full Core programs” – emerged as viable substitutes for commercial products. If a district could obtain a full digital curriculum online for free (albeit without the bells and whistles of a publisher’s platform), it put even more pressure on the pricing of paid digital products. The presence of OER further entrenched the expectation that digital curriculum might be obtained at no cost.

The cultural expectation of “digital should be free (or cheap)” extended into the classroom as well. Teachers grew accustomed to free apps, free content websites, and free trials proliferating in the ed-tech space. For K–12 publishers who historically sold to districts, this grassroots habit of free digital tools made it harder to convince end-users that a paid platform was worth the money. As one veteran Florida teacher put it when asked about going all-digital, “If they went all-digital, I would not be a happy camper” – implying that without a clear value beyond what print provides, digital alone wasn’t compelling enough, especially if it came with new costs or complexities.

In summary, educational publishers inadvertently trained their customers to devalue digital content. By positioning digital as an add-on rather than a core product, they set a price expectation of zero. Breaking that mindset has proven difficult, even as digital resources have become far more advanced and expensive to produce.

The Revenue and Margin Squeeze in the Digital Era

As the industry shifted into the 2010s, the financial repercussions of the “free digital” legacy became apparent. Publishers were pouring significant investment into new digital platforms – interactive online textbooks, learning management systems, data analytics dashboards, adaptive practice programs – but finding it challenging to get customers to pay directly for them. The old model of recouping digital costs through print sales started to falter as schools began demanding digital-first solutions (and in some cases, trying to trim print costs).

For companies like Pearson and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, this created a squeeze on margins. The development and maintenance costs of digital platforms are substantial – think ongoing software development, cloud hosting, content updates, and customer support – far exceeding the one-time cost of pressing a CD-ROM. But when customers perceive those digital offerings as “free ancillaries,” it’s hard to charge what’s needed to make a profit.

There’s also the issue of sales and pricing models catching up to reality. In the print textbook era, a big adoption (say, a state buying a new math series) was a one-off capital expense with predictable margins. Digital products often work on a subscription or annual license model, which is new territory for many school systems and publishers alike. At first, publishers often bundled digital access “free for the first year” with a textbook sale and only later tried to upsell renewals or additional digital licenses – frequently encountering resistance. By initially giving it away, they undermined their ability to later say “this piece is worth $X per student per year.”

The financial strain was evident in industry moves. Pearson, once the world’s largest education publisher, responded by restructuring and doubling down on digital delivery – but not without pain. In 2013 Pearson actually merged its consumer publishing arm (Penguin) with Random House expressly to focus on digital learning and education services. This was a strategic acknowledgement that the future was digital, but also a way to free up resources for that transformation. Former Pearson CEO John Fallon famously began shifting Pearson’s higher education business to a “digital-first” model in the late 2010s, even reducing new print editions. The current CEO, Andy Bird (a former Disney executive), has continued that push with an emphasis on subscriptions and lifelong learning. Bird draws an analogy to the music industry: “We’ve gone from iTunes to Spotify, where now we as consumers would much rather pay for access than ownership”. He suggests education will undergo a similar shift – from buying textbooks (ownership) to paying for ongoing access to digital services. That sounds promising, but it also underscores how different this is from the old bundling approach. Pearson is essentially trying to retrain its customers’ habits: get them to subscribe to a service (like Pearson+ or other digital platforms) rather than assume they own a product that comes with free extras.

At Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the story is similar. HMH emerged from a bankruptcy in the mid-2010s and explicitly repositioned itself as a “pure-play learning technology company” by 2020. The company’s CEO, Jack Lynch, has highlighted key metrics to prove the pivot: for example, in 2020, HMH saw SaaS billings grow 142% and digital platform usage jump 306% as schools flocked to its online offerings during the pandemic. Impressively, by that year half of HMH’s K–12 education billings came from “connected sales” (integrated digital+print deals). Lynch noted this positioned HMH “amongst the largest and fastest growing companies in the edtech market”. Translation: HMH was finally selling digital in a significant way. But getting there required heavy investment and a strategic overhaul. It also meant gradually convincing districts to pay for software-as-a-service rather than just buying books. The CFO of HMH pointed out that the company had to watch expenses and improve margins even as revenue shifted from one-time sales to recurring streams – a balancing act many publishers are now familiar with.

Scholastic, which historically derived a chunk of revenue from things like book fairs and clubs, also recognized the need to blend digital into its offerings – especially on the education side of the house. In recent years, Scholastic has talked up “blended literacy programs” that combine digital and print components as a key pillar of its strategy. That quote from Scholastic’s leadership in 2023 – “Investing to grow Education Solutions with new blended literacy programs, which combine digital and print components, is a key pillar of [our strategy]” – highlights that even a company famous for paperbacks and flyers sees its growth in hybrid offerings. Implicit is the understanding that the digital part of those programs must carry its weight in revenue. (Scholastic’s challenge will be somewhat different, as they often deal directly with teachers and parents in addition to school systems, but the principle of not giving away value still applies.)

In summary, the years of free digital content created a hangover that publishers have had to sober up from. It depressed what the market was willing to pay for digital just as publishers needed those revenues to take off. It’s telling that investors and executives became most excited about the education business when it promised scalable digital growth. As Scholastic’s longtime CEO Dick Robinson observed as far back as 2013, investors were “most interested in… the education side” of the business because they “see secular change” there. The implication: Wall Street expects that selling tech and services (not just books) will unlock new value. But to capture that value, publishers first had to dig themselves out of the hole of their own making – a market used to getting digital content for free.

Industry Voices: Reckoning with a Digital Paradigm Shift

It’s worth listening to the people at the helm of these companies, because they’ve openly grappled with this tension between free content and sustainable digital models. Many have spoken in candid terms about the need for transformation.

Pearson’s CEO Andy Bird, for one, has emphasized the need to reinvent the learning experience to justify new business models. Bird points out that Pearson “creates intellectual property” that “used to take the form of textbooks,” but now “that can become much more immersive, much more engaging, much more media-like”. The subtext is clear: digital learning products have to offer a different, richer value proposition than a static book+CD bundle. Bird has championed the idea of moving to an access-based model for content (hence the Spotify analogy mentioned earlier), and Pearson’s strategy under his leadership is very much about making digital content so engaging and effective that customers will pay for continuous access. He also notes the pandemic accelerated customers’ willingness to embrace digital, saying in 2021 that there’s a “massive transformation” underway in how people learn, and Pearson is undergoing a “digital overhaul” to meet it. Part of that overhaul is enterprise and workforce training in Pearson’s case, but in the K–12 and higher-ed realms, it’s about shifting from selling products to delivering outcomes and services.

HMH’s Jack Lynch has been especially vocal about balancing tech and teaching. One of his oft-repeated phrases is that we must move from “digital promise to digital proof.” In a 2021 op-ed, Lynch highlighted that after a year of remote learning, teacher confidence in ed-tech was at an all-time high, with 95% of teachers seeing benefits from educational technology and 77% believing tech will help them be more effective post-pandemic. “We’re moving from digital promise to digital proof,” he wrote, noting that educators are increasingly looking for evidence of impact. This is a crucial insight: if publishers can prove that their digital tools improve student engagement or outcomes, schools will be far more willing to pay for them. Lynch also rejects a false choice between technology and teachers, advocating a “high-tech and high-touch” blended future. This philosophy aligns with how publishers now pitch their digital wares – not as replacements for teachers or simple add-ons, but as integrated solutions that save teacher time or personalize learning in ways teachers alone cannot easily do. Lynch’s perspective is that technology must be human-centered to be accepted: “Technology alone can be isolating, but we can fuse the power of technology with the tried-and-true social gathering of the classroom”. For product leaders, that means designing digital products that complement classroom practice (and marketing them as such), rather than expecting a school to buy tech for tech’s sake.

And what about Scholastic? After the passing of long-time CEO Dick Robinson in 2021, there’s been a leadership transition, but the company’s direction on digital is evident. Scholastic’s interim CEO in 2023, Peter Warwick (with Board Chair James Polcari), underscored a focus on blended literacy solutions – essentially hybrid print/digital programs – as a growth driver. That suggests Scholastic is aiming to monetize digital by embedding it into their core literacy offerings for schools, rather than treating it as a separate freebie. It’s a recognition that even for younger grades (where Scholastic has strength, e.g. K–5 literacy), a purely print product is no longer sufficient in the eyes of many educators – nor is a digital component something to give away without charge. The company has been investing in digital subscription services for teachers (like Scholastic Teachables, Literacy Pro, etc.), which indicates a strategic move to get recurring revenue from value-added digital content, not just one-time book sales.

Lastly, it’s telling to hear an ed-tech startup leader’s voice in contrast. Mark Angel, CEO of Amira Learning (an AI-powered reading tutor that HMH invested in and later fully acquired), said in 2024: “Last generation edtech brought digital content and data. Amira is focused on the next evolution: using AI and cognitive science to deliver actionable insight to teachers and interactive tutoring to students.”. His framing of “last generation edtech” versus the new AI-driven approach captures the industry’s trajectory: we went from simply digitizing content (often given away) to now leveraging AI for real-time personalization. The latter is inherently more complex and valuable – and presumably worth paying for if it demonstrably improves learning. Angel calls Amira’s solution a “teacher’s co-pilot” that makes the tough job of instructing 20+ students more doable. That’s the kind of language that convinces school administrators to allocate budget for a digital tool: it solves a pain point that a book alone cannot.

The common thread in these voices is the emphasis on value, outcomes, and integration. The era of free digital trinkets is over – or at least, it needs to be, if publishers are to survive and thrive. As Andy Bird noted, just putting content in digital form isn’t enough; it has to be more “medialike” and engaging. As Jack Lynch implies, it has to prove itself with data (show evidence of learning gains or efficiency). And as Scholastic’s strategy suggests, it has to be woven into the fabric of instruction (blended into curriculum with both print and tech). Publishers now publicly acknowledge that digital transformation is strategic, not just tactical. Or in the words of one industry CEO (from outside K–12), “Digitization is tactical; transformation is strategic.” The K–12 publishing sector is finally taking the strategic steps to treat digital as a core business – which means charging for it in a way that customers recognize the value they’re getting.

Adaptive Learning and AI: A New Value Proposition for Digital Products

If there is a silver lining to the struggle of monetizing digital content, it’s this: today’s digital products are exponentially more powerful than the CD‑ROM add-ons of yesteryear. Adaptive learning systems and AI-driven educational tools are game-changers in terms of the value they can deliver. They offer personalized, data-informed instruction that a static textbook never could. This is the key to shifting customer mindsets – from seeing digital as a throw-in, to seeing it as indispensable.

Adaptive learning technology, often powered by algorithms that adjust to a student’s performance in real time, can help each student in a class progress at their own pace. In early literacy or K–2 math, for example, an adaptive program can give extra practice on the specific letter sounds or math facts a student hasn’t mastered, while accelerating another student who’s ready for a challenge. The result is a more efficient learning process and often better outcomes on average. These tangible outcomes are what justify a price tag. It’s one thing to ask a district to pay for a digital version of a textbook (hard sell if the print book was doing an okay job). It’s another to sell them a “personalized learning platform” that guarantees every child will stay on track or even get ahead.

We’ve begun to see evidence that such platforms can deliver on their promises. Teachers themselves acknowledge the upside of well-designed digital tools. In HMH’s 2021 educator survey, the top benefits teachers experienced with ed-tech were “improved student engagement; differentiated, individualized instruction; and flexible access to content,” reported by over 80% of educators. In other words, teachers value tech that increases engagement and personalizes learning – precisely the strengths of adaptive and AI-based systems. This positive experience is translating into willingness to use, and thus pay for, such tools. The same survey found teacher confidence in using ed-tech had never been higher. When 95% of teachers have seen ed-tech benefit students, it becomes much easier for administrators to justify expenditures on digital platforms that work.

AI-powered personalization is the latest evolution here. Modern AI (including machine learning models and, more recently, generative AI) can analyze vast amounts of student performance data to tailor instruction with uncanny specificity. It can also save teachers time by automating certain tasks. For instance, Pearson has started to integrate AI into its higher-ed products by providing AI-generated summaries of video lessons and AI-generated practice questions, available exclusively to subscribers of its Pearson+ digital platform. By doing so, Pearson is adding premium value to its paid subscription – something you certainly don’t get for free with a printed textbook. Andy Bird emphasized that using Pearson’s own proprietary content to train these AI features adds reliability and value for learners. So a student using Pearson+ might have an AI tutor that can quickly clarify a concept or generate a quiz on the fly. That’s a far cry from a static PDF on a CD, and it’s a service one can imagine students (or their parents or schools) paying for as part of a subscription. It’s a clever way to start monetizing AI: by making it a feature that enhances the overall learning product.

In K–12, adaptive learning programs in math and reading have shown especially strong results, which helps build the case for monetization. A case in point: HMH’s Amira Learning, an AI reading tutor for early elementary grades. Amira listens to students read aloud, uses AI to assess their fluency and misunderstandings in real time, and then provides 1:1 tutoring and practice tailored to their needs. According to the company, Amira’s AI tutoring has delivered reading growth rates up to 50% faster than traditional methods (with effect sizes of 0.4 to 0.8, which are considered significant in education research). In one independent study with the Utah state education department, students who used Amira for just 30 minutes per week achieved 1.5 years of reading growth in a single school year. These are eye-opening outcomes. When a digital product can credibly promise that it will help get struggling readers on track (or accelerate strong readers) in a measurable way, school districts are far more inclined to invest budget in it. Indeed, outcomes like these flip the narrative: Can schools afford not to pay for this tool? – especially when faced with post-pandemic learning gaps.

Another example comes from adaptive math software in the market. DreamBox Learning, an independent K–8 math platform (not owned by a traditional publisher until recently), has long touted studies showing that using DreamBox for a certain number of lessons per week correlates with higher test scores. Similarly, McGraw Hill’s ALEKS, an adaptive system for math and science, has been credited with improving course pass rates in higher education by targeting each student’s knowledge gaps. McGraw Hill (which also brands itself as a “learning science” company now) found that coupling their textbooks with an adaptive practice system could significantly increase student success, which supports their sales of digital platform licenses. These successes by specialized ed-tech firms put pressure on the big publishers to develop or acquire similar capabilities – and crucially, they give publishers concrete value props to sell. The pitch moves from “buy our textbook (and we’ll throw in some software)” to “license our adaptive learning system that will raise proficiency by X% – and by the way, it comes with aligned print materials.”

AI isn’t only about adapting content; it’s also enabling new feature sets that increase the stickiness of digital products. Take the example of AI-driven feedback in writing. HMH recently acquired a company called Writable, which offers a platform for students to practice writing with guided feedback. Pair that with an AI that can coach students on their essays (think of it like a safe, education-specific version of ChatGPT giving suggestions), and you have a writing product far beyond a workbook. If a district sees that an AI writing assistant leads to students writing more and improving their skills, that digital product starts to feel as essential as having an extra teaching aide in the classroom. Again, that’s worth paying for. HMH’s Jack Lynch noted that AI in education should be about saving teachers time and fitting into their workflow. A well-integrated AI that might, say, grade short-answer questions or recommend enrichment for each student frees teachers to do more personalized coaching – a selling point both for the technology and for the administrators holding the purse strings.

It’s also important that AI and adaptive systems provide ongoing data that demonstrates their efficacy. Administrators love dashboards that show usage and progress. Modern platforms come with robust analytics: they can show that 80% of students improved in a certain skill after using the program for a month, for example. These data not only help educators adjust instruction, but also help publishers prove ROI (return on investment) on their product. When renewal time comes, a rep can point to the district’s own improvement data attributable in part to the software. That’s a powerful argument, and it’s a new one – you certainly couldn’t directly measure how much a free CD-ROM contributed to test scores back in 2005. Now, with adaptive platforms, you often can make a data-driven case for impact.

To be clear, adaptive learning and AI are not a panacea for publishers’ business woes. They come with their own development costs and risks (e.g. AI accuracy, data privacy concerns). And there’s a caution not to “over-index” on AI as a cure-all. Lynch himself warned that while using AI as a personal tutor is a great advancement, “it isn’t the answer to education’s challenges” and you “can’t replace an educator”. The role of these technologies is to augment, not supplant, the human touch in education – hence his “high-tech, high-touch” mantra. However, from a business standpoint, if high-tech can truly augment high-touch, it opens up new revenue streams that simply did not exist in the old print-centric model.

The key for publishers is to design these adaptive and AI-rich products in a way that aligns with actual classroom needs (so they get used, produce results, and get renewed) and to price them in a way that reflects their enhanced value without alienating budget-sensitive schools. We’re already seeing creative approaches: subscription bundles, site licenses, per-student pricing tiers, even results-based pricing in some cases. The good news is that after a decade of stumbling in the dark, publishers now have something compelling to sell – something fundamentally different from the free extras of the past.

Case Studies: When Personalization Drives Adoption and Revenue

It’s instructive to look at a few mini case studies where a shift to adaptive or AI-enhanced products has yielded success, whether measured in learning outcomes, adoption rates, or revenue growth. These examples illustrate how publishers (or ed-tech partners) can turn the promise of personalization into tangible wins:

-

HMH’s Amira Learning (AI Tutor for Early Literacy): We discussed Amira’s learning impact above (50% faster reading growth, etc.), but from a business perspective, Amira has been a cornerstone of HMH’s digital strategy in the early grades. HMH initially invested in Amira and offered it as part of their connected solutions; the positive results and demand led HMH to acquire the company outright in 2022. By integrating Amira into its core literacy programs, HMH made those programs more attractive – a district adopting HMH’s reading curriculum could justify the purchase by citing the built-in 1:1 AI tutor. This has likely contributed to HMH’s increase in recurring digital revenue. It’s notable that Amira (and its partner Istation) now claims to serve 15% of K–12 students in the U.S. and over 1,800 districts, a rapid scale-up over just a few years. That translates into subscription licenses and ARR (annual recurring revenue) that HMH can count on, whereas a decade ago HMH had virtually no recurring subscription revenue in early literacy – it was all one-time textbook sales.

-

Savvas (formerly Pearson K12) and Realize Platform: When Pearson sold its U.S. K–12 curriculum division to private equity in 2019 (now operating as Savvas Learning Company), one of the crown jewels of that business was the Savvas Realize platform – a digital hub for delivering all the content and adaptive assessments for their programs. Realize was part of every adoption deal, and over time, customers began to see it not just as a bonus but as the core of the program (with the print textbooks as supports). Savvas has continued to invest in Realize, adding AI capabilities and integrations. By all accounts, the usage of the platform is huge (millions of students), and it has helped Savvas secure multi-year district contracts that bundle content with platform access. This has shifted the revenue model toward multi-year subscriptions. While specific numbers are proprietary, Savvas’s strategy indicates that districts are indeed now paying for platform access beyond the initial adoption period, especially if the platform provides ongoing updates, analytics, and adaptive practice that teachers rely on.

-

Cengage Unlimited (Higher Ed, but instructive): In higher education, Cengage (not a K–12 publisher, but an analogous case) introduced an all-you-can-eat digital subscription for students called Cengage Unlimited in 2018. Within the first full academic year, they sold over one million subscriptions, signaling student willingness to pay for affordable digital access when the value proposition is clear (unlimited access to a library of e-textbooks and courseware). This model has been watched closely by K–12 content providers. While K–12 purchasing is very different (schools/districts pay, not individual students), the principle of bundling digital content into a subscription is being emulated in offerings like Pearson+ for higher ed and could foreseeably extend to K–12 district-wide subscriptions for digital content libraries or adaptive services. The success of Cengage’s model suggests that with the right pricing and perceived value, even a market used to expensive textbooks can shift to subscriptions – a hopeful sign for K–12 publishers contemplating similar moves.

-

McGraw Hill’s ALEKS and Connect: McGraw Hill Education has reported that institutions using their Connect platform (which includes SmartBook, an adaptive e-book technology) see higher rates of student retention and performance in certain courses. Connect and ALEKS are often sold as separate digital products, and McGraw Hill has managed to grow its digital revenue to exceed its print revenue in higher ed. For K–12, McGraw Hill has similar adaptive components in its Wonders (ELA) and Reveal Math programs. The proof point often cited is that these adaptive tools help raise test scores or proficiency rates, which in turn encourages districts to renew and even expand their usage. McGraw Hill’s CEO Simon Allen noted that 90% of their new adoption wins include a digital component, reflecting that no deal is really just about print anymore. This ubiquity of digital in sales is partly because the adaptive/personalized pieces are now seen as essential by customers. The outcome is that McGraw Hill can drive continuous revenue (in the form of platform fees, maintenance, or per-student licenses) beyond the initial sale.

-

Scholastic’s Blended Literacy and Digital Subscriptions: Scholastic’s recent blended literacy programs (such as a new core literacy curriculum with both print books and an adaptive digital app) are still in the early phase of rollout. But a historical example from Scholastic is their Lexia Learning product. Lexia (a reading intervention software) was acquired by Rosetta Stone and then by Cambium, but for a period in the early 2010s Scholastic had a distribution partnership with Lexia. Schools were willing to pay for Lexia’s adaptive individualized practice because it was proven to help struggling readers. Scholastic saw the writing on the wall that such software had strong standalone demand. Today, Scholastic’s strategy seems to be developing its own comprehensive literacy solution that melds the best of its print content (decodables, libraries of leveled readers) with assessment and personalization tech. If they succeed, the result will be a program that schools buy not because “it comes with a cool piece of software for free,” but because “this integrated solution will raise our reading scores and is worth the price.” We already see hints of this in Scholastic’s messaging about addressing learning gaps and incorporating social-emotional learning with digital tools.

Each of these cases reinforces a lesson: when digital tools demonstrably improve learning or teaching efficiency, customers recognize their value – and will pay accordingly. The challenge, of course, is to maintain that efficacy and not over-promise. Because the flip side is also true: if a product doesn’t live up to the hype, it will be discarded (there have been plenty of abandoned “adaptive” products that couldn’t show results). But as long as publishers and ed-tech providers continue to iterate and leverage AI in thoughtful ways, the trajectory points to more success stories.

The Path Forward: From Free to Fee – Strategies for Monetizing Digital Learning

Having examined the past missteps and the current opportunities, how can educational publishers move forward in a way that overcomes the legacy of free digital content? Here are several strategies and considerations for product managers, digital strategists, and executives in the educational publishing sector:

1. Lead with Outcomes, Not Features: The era of selling digital tools on novelty (“it’s interactive!”) is over. Today, a school administrator (and certainly a school board or state official) needs to hear how a product will move the needle on student achievement or teacher effectiveness. Publishers must rigorously pilot and gather data on their digital offerings. These results should drive marketing and sales conversations. If a math platform can show it reduces the failure rate in Algebra I by 30%, that outcome justifies its cost in a way that “includes 100 videos and games!” never will. This outcomes-driven approach flips digital from a perceived cost center to a high-impact investment. In practice: publish efficacy research (many companies now have “research centers” or white papers), share case studies from districts, and even consider performance-based pricing models (e.g. “if usage and scores don’t improve as promised, we’ll offer discounts or additional services”). This builds trust that the publisher is a partner in improvement, not just selling software licenses.

2. Bundle Smartly (Print + Digital + Service): Instead of the old model of bundling digital as a free extra, the new model is bundling as a value multiplier. That is, offer integrated packages that combine print materials, digital platform access, and professional development or service in one price. This way, the digital component isn’t seen as free; it’s one pillar of a comprehensive solution. For example, a literacy program might come as a “blended learning package” that includes a set of physical books, yearly subscriptions to an adaptive reading app, and training sessions for teachers on how to leverage the data reports. The price is for the package as a whole (with multi-year subscriptions baked in). Many districts prefer to buy this way now, as it simplifies purchasing and ensures all components work in sync. It’s also easier to find funding for a “complete literacy improvement solution” than to separately justify a line item for a digital platform. The key is to avoid itemizing the digital as $0 – it should have an evident share of the value in the bundle. As Scholastic’s leadership hinted, the future of their Education Solutions lies in combined digital and print programs, which likely will be sold as one solution, not a la carte pieces.

3. Embrace Subscription and Recurring Revenue Models: Publishers need to continue the shift from one-time sales to recurring revenue, but do it in a customer-friendly way. Annual per-student or per-school subscriptions for digital content are becoming the norm. The Spotify analogy from Pearson’s Andy Bird is apt – customers may pay continually, but they expect continuous updates and improvement in return. This means content updates, feature updates, and responsive customer support have to be part of the offering. It’s a different rhythm: instead of a big push every few years for a new edition, it’s a steady relationship with the customer. Publishers should invest in customer success teams and onboarding, similar to SaaS companies, to ensure schools use what they buy (high usage leads to high renewal). The payoff is more stable revenue and deeper integration into instruction (which also raises switching costs, to be blunt). Pearson’s introduction of things like Pearson+ (a monthly student subscription model) and HMH’s tracking of Net Retention Rate are signs that even giants are redesigning their KPIs around recurring usage and revenue, not just pipeline of new adoptions.

4. Differentiate with AI and Human Support: The best digital products going forward will likely blend AI-driven personalization with human expert support. For instance, an AI might handle routine personalization and data crunching, but the publisher could offer on-demand access to instructional coaches or tutors (perhaps for an extra fee). This hybrid model ensures that the technology is always aligned to real classroom practice. It also creates a premium tier of service that can be monetized. Imagine a district paying not just for a math software license, but for a “math success package” that includes the software plus quarterly consults with a math specialist provided by the publisher to analyze student data and recommend interventions. This moves the publisher into a partner role in implementation, which schools value immensely. It’s hard to walk away from a vendor who is helping you succeed on an ongoing basis. This strategy also mitigates the risk that a school buys a fancy adaptive program and doesn’t know how to implement it well (leading to poor results and non-renewal). By ensuring high-touch support to complement the high-tech tool, publishers can secure both better outcomes and loyal customers.

5. Continue to Offer Freebies – Strategically: Counterintuitive as it may sound, “free” isn’t going away as a marketing strategy, but it must be used wisely. Rather than giving away core value, publishers can offer free trials, freemium tiers, or limited-time access to showcase what their digital products can do. During the COVID-19 shutdowns, many publishers offered free access to digital resources for a few months – which in some cases actually boosted later adoption when schools decided to purchase the full product after seeing its impact. The difference now is being deliberate: give something for free that leads users to experience the value and then convert to paid. For example, a publisher might allow teachers to use an AI homework help tool for free, but the full dashboard and adaptive learning path for students is part of the paid version. Open-ended free content (like general lesson ideas or a handful of activities) can still serve to build brand goodwill (Scholastic has long done this with its teacher site). But the line between free and paid should be clearly tied to depth of value. Open Educational Resources will continue to exist, but publishers can distinguish their paid content by wrapping it in adaptive technology, assessments, and seamless integration – things that OER often lack. As one industry observer put it, traditional publishers are looking to “co-opt the open textbook revolution” by layering services on top of free content. Whether that’s via OER+ premium add-ons, or simply making their own content significantly better through tech, it’s a path to ensure free alternatives don’t completely undercut them.

6. Align Pricing with Outcomes and School Budgets: Finally, product strategists must set pricing in line with educational value and budget realities. This might mean offering flexible models like per-student pricing (so a small district can afford a platform without buying a minimum license for 500 students), volume discounts, or even results-based guarantees. In the long run, if an AI-driven platform genuinely replaces the need for certain supplemental staff or improves efficiency, publishers should articulate that value in financial terms. For instance, if a reading AI tutor reduces the need for as many reading intervention periods, a district might reallocate budget to the software. Being creative and empathetic to how schools allocate funds will smooth the transition from free to fee. It also helps to position digital expenditures not as tech spending for its own sake, but as part of the academic improvement budget or the equity strategy (e.g., closing learning gaps, which many districts have special funding for post-COVID). The more directly a digital product ties to a district’s strategic goals (reading proficiency by 3rd grade, algebra readiness, etc.), the more protected its funding will be. Thus, pricing and product development should be guided by those key metrics and goals.

Turning a Cautionary Tale into a Success Story

Educational publishing’s journey with digital content has certainly been a rocky one. What began as a marketing tactic – giving away CDs and online extras to sell more books – nearly turned into an existential threat as it devalued the very digital innovations that now must drive the industry’s future. The “free digital” era will be remembered as a cautionary tale in product strategy: it’s a vivid example of how short-term decisions to boost adoption can create long-term pricing expectations that are hard to unwind.

Yet, the story doesn’t end there. The same industry that inadvertently taught customers to expect digital for free is now actively reshaping its value proposition through adaptive learning and AI. This new generation of digital products is not just flashy content but a fundamentally different educational experience – one that can deliver personalized learning at scale, provide proof of efficacy, and help educators meet challenges that a textbook alone could never solve. In doing so, publishers are finally offering digital solutions that stand on their own merits (and revenue models), rather than riding sidecar to print.

There is a convergence happening: publishers are becoming tech companies at the same time that schools are becoming more data-driven and outcomes-focused. The pandemic’s forced experiment in digital learning accelerated acceptance of technology in the classroom, but it also raised expectations – technology must earn its keep by demonstrably supporting learning. The encouraging news is that many publishers, big and small, have started to crack this code. They are reporting growth in recurring digital revenues, greater usage of their platforms, and improved student results linked to their products. In the words of HMH’s CEO Jack Lynch, educators now largely agree that tech can make them more effective, and the task ahead is to provide “digital proof” of impact.

For product managers and digital strategy leaders reading this, the mandate is clear: build and market digital learning tools that are so good, they sell themselves on value – not as freebies, but as must-haves. This means continuing to invest in AI and adaptive capabilities, but also investing in research, teacher training, and support to ensure those tools are used to full effect. It means pricing creatively and fairly, shedding remnants of the old bundle mentality. It also means staying agile – learning from the ed-tech upstarts, partnering or acquiring where it makes sense (as seen in the wave of M&A like HMH with NWEA and Amira, or Pearson with its AI initiatives).

In a sense, the industry is coming full circle. The early 2000s had publishers exploring digital with gimmicks and giveaways; the 2020s have them harnessing digital with purpose and profit in mind. If the current trends continue, we might soon see a time when a publisher’s biggest revenue generator is a digital subscription or an AI-driven platform – and no one bats an eye at paying for it because the value is evident every day in the classroom. In fact, we’re nearly there: Pearson’s own vision is to make learning a lifelong, subscription-oriented experience.

Ultimately, what will make this transformation stick is a win-win outcome: students learn better, teachers teach better, and publishers find sustainable growth. The customers (schools and learners) will gladly pay for products that truly move the dial, especially as older attitudes fade and new tech-native administrators take the reins. The free rides of the past are being replaced by fare-based journeys – but if those journeys reliably lead to improved student success, most will agree the ticket price is worth it.

The educational publishing sector has learned a hard lesson about undervaluing its own digital content. Now, armed with adaptive learning, AI personalization, and a clearer focus on outcomes, it has the tools to redefine that value in the eyes of customers. The transition from “free” to “fee” isn’t easy, but it is necessary – and with the right strategy, it’s proving to be possible. As we move forward, publishers who can combine the creativity of tech innovation with the wisdom of educational experience will be the ones to turn this ship around. They’ll not only recoup the monetization opportunities once lost, but also deliver on the long-awaited promise of digital learning. In doing so, they’ll transform a cautionary tale into a success story for the digital era.

How Adaptemy is Helping…

The Adaptemy team has held various positions within Educational Publishers for over 20 years. Our background gives us a unique understanding of the opportunities (and challenges) Educational Publishers face.

To learn more about how our solution can deliver results for your team, visit: Adaptive Learning for K-12 Educational Publishers

Sources:

-

John Smith & Son study on print/digital bundling successresearchinformation.inforesearchinformation.info.

-

UK Competition Commission report on blended products in K–12 publishingassets.publishing.service.gov.uk.

-

Education Week survey data on affordability as a barrier to digital contentmarketbrief.edweek.org.

-

HMH Annual Report noting open educational resources (free digital) as competitionannualreports.com.

-

Andy Bird (Pearson CEO) on shifting to “access” (Spotify model)businessinsider.com.

-

Andy Bird on transforming learning beyond textbooks to immersive mediabusinessinsider.com.

-

Jack Lynch (HMH CEO) on moving from “digital promise to digital proof” and teacher confidence in ed-techhmhco.comhmhco.com.

-

HMH 2020 results – digital usage growth, ARR, and Jack Lynch quote on digital adoptionhmhco.comhmhco.com.

-

Scholastic leadership (Polcari) on blended literacy programs (digital+print) as strategic pillarpublishingperspectives.com.

-

Dick Robinson (Scholastic CEO, 2013) on investors’ interest in ed-tech and doing more with tech programsbambooinnovator.com.

-

TechNewsday report on Pearson’s AI integration (Bird’s plan for AI summaries & questions in Pearson+)technewsday.com.

-

Authority Magazine interview – Jack Lynch on AI as a teacher’s aide and not replacing educatorsmedium.commedium.com.

-

Amira Learning press release – Mark Angel (CEO) on next-gen AI tutor and 50% faster reading growth with AIamiralearning.comamiralearning.com.

-

Amira Learning press release – independent study: 30 min/week with Amira = 1.5 years reading growthamiralearning.com.

-

Publishing Perspectives on Cengage Unlimited’s early success (1+ million subs)publishingperspectives.compublishingperspectives.com.

> If your team is committed to improving learning and training with AI, you can book a virtual meeting with Adaptemy here: